In line with the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, the Klau Center presented a series of events aimed at investigating various aspects of the games from a human rights perspective. “Behind the Games: Human Rights and the Olympics” explored historic boycotts, China’s use of human rights language to deflect from its policies, and the racial tensions surrounding the 1968 Olympics.

“Proponents of the Olympics often take the view simultaneously that politics and sport should be separate and that sport can help promote positive change in human rights and political issues and help reform dictatorships.”

Notre Dame history professor John Soares kicked off the series on January 26, explaining the social and political reasons for the boycotting of past Olympic games, the impact of these boycotts, and how these issues contextualize the present moment.

"Proponents of the Olympics often take the view simultaneously that politics and sport should be separate and that sport can help promote positive change in human rights and political issues and help reform dictatorships," Soares said. In his exploration of the Olympic boycotts of the 20th century, Soares noted that while dictatorships tend to treat hosting the games as an endorsement of their politics, the games invariably draws attention to human rights issues.

Regarding the Biden administration’s diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Games, Soares said he understands there is a limited amount of external pressure that can be placed on the Chinese government. But, he said, Biden “…may have found a way to kind of thread the needle for that correct balance that will get Chinese attention without hurting his own people and without playing into narratives on the Beijing leadership that they’re being picked on unfairly.”

“…we’re going to see more than democratic backsliding; we’re going to see human rights eradication.”

The series continued on February 10 with professor Diane Desierto, who examined China’s “recasting of human rights to suit its own mold with respect to its own philosophical, ethical, and geopolitical considerations.” While ratifying numerous UN human rights conventions, for instance, China nonetheless rejects the compliance procedures contained within them. The result is that while appearing to support an international consensus on human rights, China reserves the right to adjudicate its own offenses according to its own internal logic.

In conversation with professor Joshua Eisenman, Desierto explained the dangers of this rejection of universal definitions. “In the 1990s there was an overwhelming rejection of the approach to dumb down universality…this time around, when democratic backsliding has led to about 60% of the world being either autocratic or semi autocratic, China has more allies in seeking this reinterpretation.”

While acting as host to the supposedly non-political Olympic games, then, China nonetheless frames human rights as a political intrastate issue rather than a universal human issue. “If this is all based on the political compromises that could be made by states, we’re going to see more than democratic backsliding; we’re going to see human rights eradication.”

"...by the time we get to the 1960s...Black communities have seen cycles of failure and false starts in galvanizing real structural transformation at the nexus of race and power.”

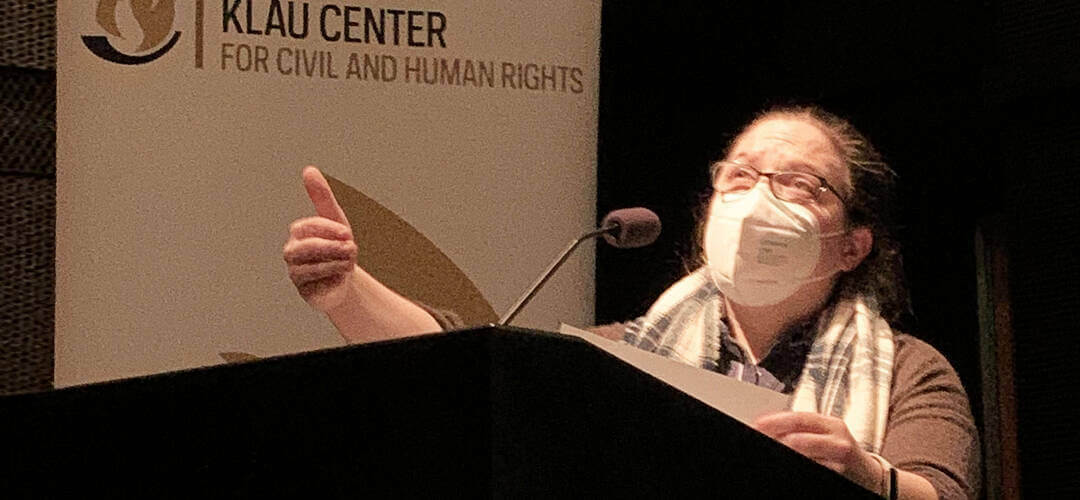

Concluding the series January 15, professor Katherine Walden offered deep historical insight into the 1968 Olympics for a screening of the documentary “The Stand: How One Gesture Shook the World.” Marked by the racial tension that surrounded them, the games are best remembered for the symbolic raised fists that runners John Carlos and Tommie Smith offered on the Olympic podium.

Walden’s introduction opened this moment up to more thoughtful consideration by placing it in context of a continuing struggle for racial justice in the US, connecting these struggles with an incongruous image of liberal “American values” abroad. “So,” Walden explained, “by the time we get to the 1960s not only is the larger national conversation changing around the politics of patriotism and protest (civil rights movements, Vietnam War, etc.) but Black communities have seen cycles of failure and false starts in galvanizing real structural transformation at the nexus of race and power.”

Reflecting on the broader political alliances that the 1968 Olympics brought to the fore, Walden finished her remarks by reflecting on the relevance that historical moment might have for us today. “I encourage folks watching to reflect on how the film asks us to think about what solidarity can look like,” she said, “as well as the cost of solidarity--and what that might mean for the work we do on this campus.”