A powerful presence on the world stage

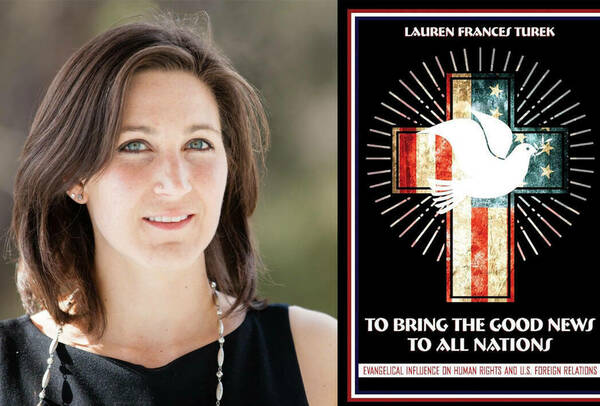

Widely thought of as advocates for a conservative domestic agenda including opposition to abortion and LGBTQ rights, evangelical Christians have also, since the 1970s, been key players in shaping US foreign and human rights policy. That revelation forms the basis of research by Lauren Turek, associate professor of history at Trinity University. Turek shared her findings with students and faculty recently at the Keough School.

Beginning in the early 1970s, a population boom in the global south had evangelical denominations worried, explained Turek, that they were falling behind in their mission to spread the Christian gospel to all the people on earth. This concern, in Turek’s view, shaped the evangelical perspective on human rights policy. “Because of the evangelical commitment to achieving the Great Commission and sharing the gospel with all the world,” she said, “they had come to see religious liberty, the freedom to evangelize and the freedom of the unreached to hear the gospel, as the most vital of all human rights. There was no earthly privation that could compare to the loss of the potential for ultimate salvation.”

Evangelicals had observed the efficacy of lobbying efforts in Congress on behalf of persecuted Jews in Russia. Inspired by this, they called on their representatives to use similar US foreign policy levers to try to make the world safe for Christian evangelism. By the time Ronald Reagan came into the White House in 1981, evangelical Christians had come together to form a large number of organizations that were focused on protecting the freedom of religion and evangelism abroad through lobbying.

Supporting abuses in the name of freedom

The extent to which singling out a single right as as the “primary human right” could potentially distort perceptions was made clear in a case study Turek presented.

In March 1976, a devastating earthquake struck Guatemala. American evangelical Christian organizations fanned out into the cities and the countryside to help the country rebuild from disaster and to spread the gospel. A brigadier general in the Guatemalan army by the name of Ephraim Rios Montt joined one of these Bible study groups and in 1979 converted to evangelical Christianity.

When a group of disillusioned young officers in the Guatemalan army staged a coup d'etat at the National Palace in Guatemala City, forming a military junta, they named Rios Montt to be one of its members. He approached the elders of his church to ask them for guidance. The elders lay hands on Ephraim Rios Montt, prayed over him, and sent him out with God's blessings to join the new junta. Through these prayers Rios Montt came to believe that God had ordained him to lead Guatemala.

Despite Rios Montt's vows to end government corruption and rampant human rights abuses, many thousands of leftist political activists, guerrillas, and Mayan civilians perished under his counter insurgency program. About 3, 000 people died per month, and thousands more were disappeared. Over a million people fled the country to escape the violence. Nevertheless, televangelists called on viewers to raise money for Guatemala and to send letters to Congress and the White House calling on them to support Rios Montt in his fight against what he had called a communist insurgency. Many US evangelicals believed that by supporting Rios Montt, they were going to help defeat communism in Central America and make it a safe haven for evangelism and the spread of their faith.

A lasting impact

Highlighting the contunuing impact of evangelical lobbying groups on US human rights policy, Turek pointed to the State Department Commission on Unalienable Rights that former President Trump's Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, launched in 2019. Its July 2020 report asserted, among other things, that foremost among the unalienable rights that the government is established to secure from the founder's point of view are property rights and religious liberty. Pompeo reiterated this idea at a ceremony where they released a draft to the public, arguing that the United States should be prioritizing the rights of religious liberty and private property above other rights.

Asked whether the groups who supported Rios Montt still believed they were correct in their assessment, Turek observed that they still seem to believe that they had done the right thing, fostering the ability to spread the gospel. “These are not necessarily contradictory. I mean it's hard to look at it and see anything other than a genocide, but we also want to understand how they were trying to frame it at the time, for themselves and for their particular policy agenda.”